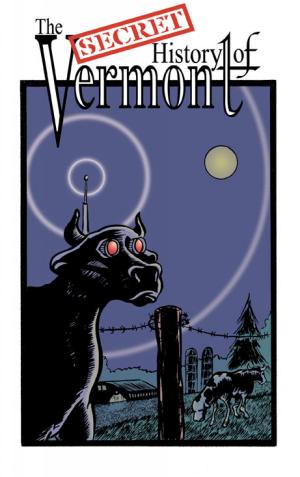

Excerpts from Richard Heurtley's best selling book "The Secret History

of Vermont" which will be published Real Soon Now.

Excerpts from Richard Heurtley's best selling book "The Secret History

of Vermont" which will be published Real Soon Now.

Text Copyright © 1999-2004 by Richard Heurtley.

Illustrations Copyright © 1999-2000 by Nathan Bliss.

All rights reserved.

Richard Heurtley's "The Secret History of Vermont" makes a mockery of the dignified field of History. It is said that those who do not study History are condemned to repeat it, but those who study this poor, thin, excuse of a book are condemned to a far worse fate: Having wasted a few minutes of their lives when they could have been doing something enriching, like reading my latest book "Annotated Minutes of the Legislatures of the Mid-Atlantic States, Session of 1887, Vol. VII."

I was born in Vermont and I remember being told some of what is related in this so-called book as a child. Fortunately my parents stopped when I made it clear that I had no tolerance for such foolishness. History is the product of reading and interpreting the work of fellow Historians and the process of Peer Review. It is not simply a random collection of bedtime stories and overheard conversations.

The organization of Academic History is a proud lineage of doctoral advisors and graduate students stretching back to Plutarch himself. The bumbling efforts of amateurs and poseurs outside this structure only serve to confuse the public. I've often thought that the word "History" itself should be somehow trademarked and licensed for the exclusive use of authorized Historians, a status for which, in my strong opinion, the author of "The Secret History of Vermont" certainly does not qualify.

Vermont has always had a population of Flatlanders: those who've moved to Vermont from somewhere else because Vermont "is such a nice place." In recent years those who pay attention to the media might conclude that Flatlanders have taken over the entire State. It is true that important Towns like Montpelier (the State capital) and Burlington (a self-styled major metropolitan city) are almost, but not quite, exclusively populated by Flatlanders.

Native Vermonters quite sensibly regard the current large numbers of Flatlanders to be a temporary phenomenon and have the attitude of "This Too Shall Pass." Like mud season. They know that as soon as it appears to the Flatlanders that Vermont has somehow, despite all their progressive efforts, become "just like everywhere else", they will move away in droves. Perhaps leaving behind a few people, who might after a few generations be considered "Newcomers" to Vermont by the Natives and occupy that wide gray area between the two solitudes, so to speak.

This book reveals for the first time the true History of Vermont as maintained by Native Vermonters. When the influx of Flatlanders started to become chronic Native Vermonters agreed in a series of Town Meetings to conceal some of the more interesting episodes of Vermont History by the simple and expedient method of denying knowledge of any such thing and implying that the questioner was a few cows short of a herd. This tactic was incredibly successful and centuries of Vermont History were hidden this way. The truth of this remarkable assertion can be demonstrated at any time by finding an older person in Vermont (Flatlanders without exception move to Florida once their joints reach a certain age and temperature) and asking that person whether he or she has heard of the events described in this book. The answer will invariably be "No." followed by something on the order of "What's the weather like on the planet you come from?"

How did the author, who moved to Vermont from California, learn of this secret history? The answer is that he inadvertently acquired two undeniable attributes of Native Vermontership as follows:

One day after walking uphill (of course) in the snow for hours into Town for a breakfast of pancakes and maple syrup the other people in the Town Restaurant began to talk about strange events in his presence. After several more days of walking uphill (of course) in the snow for hours into Town for a breakfast of pancakes and maple syrup the author began to piece together the incredible Secret History of Vermont.

Why is the author willing to reveal these incredible truths? The answer is that if he publishes a book and someone actually buys it then all those breakfasts become tax-deductible as a research expense. Free food! Everyone has their price when it comes to betraying deep secrets. That's mine.

Back in the days when the U.S. Federal Government was disorganized and

inefficient (1789 to date) it often had difficulty maintaining an

adequate supply of currency. When there weren't enough bills and coins

to go around people used commodities as a means of exchange. In

Vermont the primary commodities were, of course, maple syrup and cows.

Maple syrup was the more liquid of the two commodities but Vermont had

so many cows that it was considered at the time to be the wealthiest

State.

Back in the days when the U.S. Federal Government was disorganized and

inefficient (1789 to date) it often had difficulty maintaining an

adequate supply of currency. When there weren't enough bills and coins

to go around people used commodities as a means of exchange. In

Vermont the primary commodities were, of course, maple syrup and cows.

Maple syrup was the more liquid of the two commodities but Vermont had

so many cows that it was considered at the time to be the wealthiest

State.

The problem with cows is that they are large and difficult to store. Wealthy people had country estates on which they kept their cows but for everyone else an institution was created that would take cows for storage and maintenance. The institution would try to make money from its deposits in the form of milk and animal labor and would pay the owner interest in the form of calves. For logistical reasons that will shortly be apparent the first of these institutions was located on Bank Street which runs along the shore of Lake Champlain in Burlington. Eventually these institutions became generically known as banks.

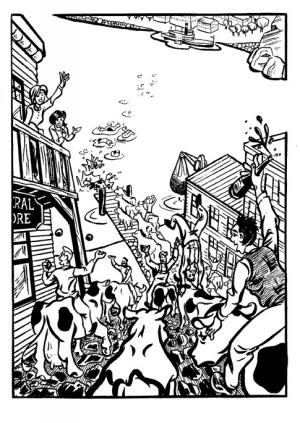

People who put their cows into a bank received certificates of deposit that then circulated as a convenient form of currency. Once a year however the banks were required by law to reconcile their accounts and a massive transfer of cows would take place. When this happened the entire Town was paralyzed by huge herds of cows on the streets so Reconciliation Day was declared an antibank holiday where everyone except bank employees got the day off.

In addition to moving cows between local banks there were foreign accounts that required reconciliation. This was accomplished by loading cows on a paddlewheel boat that would take them down the Hudson River to New York City. To do this the bank built the "Cow Wharf" next to its office on Bank Street and extending into Lake Champlain. The paddlewheel boat would dock at the Cow Wharf and the cows would be driven onto it and into the boat.

Loading the cows into the paddlewheel boat was always the last transaction of Reconciliation Day and everyone would don boots and line the sides of the streets to watch the cows go by and celebrate the end of another successful fiscal year. Shortly the beer vendors decided that watching a bunch of cows walk down the street was just way too boring and business would pick up if the cows stampeded down the street and onto the Cow Wharf instead. This proved to be tremendously popular and soon young men could be seen running ahead of the cows, trying to ride them, getting horribly injured, and generally acting like they had found a particularly potent variety of mushroom up in the woods.

Women would smile and cheer the men on and think, "This is the best way to weed out the gene pool that we've ever devised and I see that Richard, the adding machine repairman, is having nothing to do with it. I think I'll go over to his log cabin and seduce him. I'd better hurry. Last year he had to put out one of those "Please Take A Number" machines."

All of this came to a screeching halt one Reconciliation Day when the paddlewheel boat accidentally docked at the Maple Syrup Pipeline Wharf instead of the Cow Wharf and no one noticed until it was too late. The year's entire foreign account transfer stampeded into Lake Champlain and drowned. Without the annual Vermont foreign account transfer most of the businesses in New York went bankrupt which triggered a regional depression.

There was a run on the banks as people withdrew their cows fearing for the safety of their capital and many banks failed as a result. (Native Vermonters kept their own cows and weren't affected by any of this except for one who laughed so hard when he heard about it that he fell down and broke an ankle.) The paddlewheel boat company was sued until there was nothing left but a smoking hole in the lake. Its assets were sold to a foreign firm.

The only modern evidence of The Unfortunate Burlington Cow Wharf Incident is a (W) symbol sometimes seen on maps of Burlington where the Cow Wharf used to be. The author surmises that The Unfortunate Burlington Cow Wharf Incident was made part of the Secret History by Native Vermonters as a favor to Flatlanders who were only too glad to forget about the whole thing.

Before the age of the railway train it was the paddlewheel boat that

fueled commerce in Vermont. Fleets of majestic steam powered

paddlewheel boats would transport goods on Lake Champlain and the

Hudson River to the west, on the Connecticut River to the east, and on

the mighty Missisquoi River to the north. The Missisquoi River was

particularly heavily traveled because it connects Lake Champlain,

northwest Vermont, Quebec, and the western side of the Northeast

Kingdom of Vermont. Typical cargo was cigarettes and beer, the source

and destination of which changed as a function of relative tax rates;

fugitives from the Quebec Language Police; and, of course, maple syrup

and cows.

Before the age of the railway train it was the paddlewheel boat that

fueled commerce in Vermont. Fleets of majestic steam powered

paddlewheel boats would transport goods on Lake Champlain and the

Hudson River to the west, on the Connecticut River to the east, and on

the mighty Missisquoi River to the north. The Missisquoi River was

particularly heavily traveled because it connects Lake Champlain,

northwest Vermont, Quebec, and the western side of the Northeast

Kingdom of Vermont. Typical cargo was cigarettes and beer, the source

and destination of which changed as a function of relative tax rates;

fugitives from the Quebec Language Police; and, of course, maple syrup

and cows.

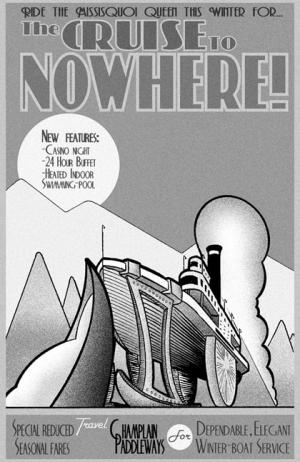

Many of the paddlewheel boats were equipped to transport passengers and offered amusements such as gambling and facilities like small expensive boutiques, 24 hour buffets, and heated swimming pools. People would spend their entire vacation on a "paddlewheel boat cruise to nowhere" although everyone had to go ashore when the boat docked at the Town of Richford.

The Missisquoi River starts deep in the Green Mountains and flows north into Quebec where it loops around back into Vermont and eventually empties into the Missisquoi Bay of Lake Champlain. The Town of Richford is located where the Missisquoi reenters Vermont from Quebec. As the paddlewheel boat industry grew so did Richford until, at its heyday, Richford was one of Vermont's largest commerce centers and the envy of the other Towns. Docks and wharves extended into the Missisquoi and hundreds of boats would be clustered around as cargo was loaded and unloaded. Luxurious passenger paddlewheel boats with names like "The Missisquoi Queen" would come and go announcing their intentions with blasts of their steam powered horns. All cargo and passengers had to be cleared by the Customs House before and after crossing the border and the Master of the Customs House was the richest and most powerful person in the Town. Local entrepreneurs capitalized on the perpetual transient population and the whole Town was lit with thousands of lights advertising large theme hotels and casinos, magnificent star-studded shows, Institutes of Adult Entertainment, and pawnshops.

The problem of keeping the paddlewheel boats running during the winter was solved in a typical Vermont fashion. Instead of trying to keep the water channels open, the paddlewheels were affixed with chains, the entire boat was mounted on sled runners, and a snowplow was attached to the front. As a result, the paddlewheel boats ran considerably faster on the ice during the winter than they did in the water during the summer. The summer slowdown was tolerated because it typically only lasted 15 days.

The era of paddlewheel boats in Vermont ended shortly after The Unfortunate Burlington Cow Wharf Incident when the paddlewheel boat company lost the resulting lawsuit and went bankrupt. Most of the paddlewheel boats were sold to a foreign firm that made use of them on a minor river somewhere down south. The single surviving example can be seen at the Shelburne Museum, but if you go there don't bother asking about paddlewheel chains, sled runners, or snow plows. Native Vermonters run the Shelburne Museum and they will deny that such things existed.

Vermont is unique among the states in that it has two completely

independent State governments. The first, known as the Vermont State

Government, has no bureaucrats, has levied no taxes, and is of the

opinion that it isn't the government's place to go around telling

people what to do. It has the highest approval ratings of any

governmental organization in the observed universe. The other is known

as the Montpelier Legislature whose motto is, "Pass six unenforceable

regulations before breakfast." Perhaps a few examples will help

illustrate how the Montpelier Legislature operates:

Vermont is unique among the states in that it has two completely

independent State governments. The first, known as the Vermont State

Government, has no bureaucrats, has levied no taxes, and is of the

opinion that it isn't the government's place to go around telling

people what to do. It has the highest approval ratings of any

governmental organization in the observed universe. The other is known

as the Montpelier Legislature whose motto is, "Pass six unenforceable

regulations before breakfast." Perhaps a few examples will help

illustrate how the Montpelier Legislature operates:

During the right time of year a visitor to Vermont cannot help but to be astonished at the amount of acreage devoted to growing corn. A simple calculation shows that during its 15 day growing season Vermont grows enough corn to feed all of Asia and Africa for several years. Where does all this corn go?

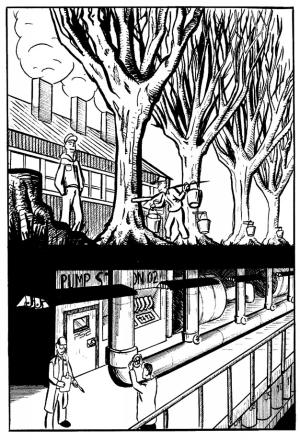

Some of it is fed to cows. Cows are no longer legal tender but cows give milk that can be made into Ben and Jerry's Ice Cream which is legal tender in most parts of the world. Some of the corn is converted into whisky most of which is discretely exported to foreign places like Kentucky and Tennessee. A very small amount of the corn is sold to tourists in quaint little roadside concessions usually consisting of a card table and a cardboard sign that says, "SWEET CORN $1/doz". This is done only to make people overlook the primary use of the corn, which is making corn syrup.

When the Montpelier Legislature, during a travel junket outside of Montpelier, saw Vermont corn fields for the first time its reaction was, "Wow! Look at all this corn! We must tax it so we can create a Department of Corn Management!" Incredibly, instead of storing corn over the winter for VDCM inspectors to find and add to the State Corn List, Vermont farmers figured out a way to hide it instead. What they do is render it down into corn syrup, which is mostly sugar; pump it into maple trees in the fall, pump it out again in the spring, all nicely maple flavored; and boil it down into maple syrup, which isn't taxed and used to be legal tender.

The idea that maple trees somehow make sugar water inside themselves is an ancient fiction created for the occasional Montpelier Legislature member who, during a travel junket outside of Montpelier, wonders where maple syrup comes from.

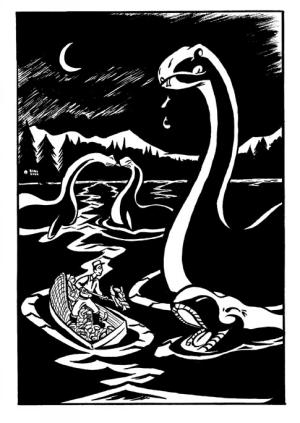

For many years there have been rumors and occasional dubious sightings

of a possible dinosaur-like monster living in Lake Champlain, much

like the monster rumored to live in Loch Ness, Scotland. The Lake

Champlain Monster has been affectionately baptized as "Champ" by the

Vermont Department of Tourist Management and has occasionally been

used as an excuse to visit Vermont by Flatlanders who, upon arrival,

stare intently at the lake for about 30 seconds and then express an

interest in the possible remnants of the historical Institutes of

Adult Entertainment in Richford.

For many years there have been rumors and occasional dubious sightings

of a possible dinosaur-like monster living in Lake Champlain, much

like the monster rumored to live in Loch Ness, Scotland. The Lake

Champlain Monster has been affectionately baptized as "Champ" by the

Vermont Department of Tourist Management and has occasionally been

used as an excuse to visit Vermont by Flatlanders who, upon arrival,

stare intently at the lake for about 30 seconds and then express an

interest in the possible remnants of the historical Institutes of

Adult Entertainment in Richford.

The facts of the matter are that these rumors are incorrect. There isn't a monster in Lake Champlain. There's a whole family of them. None of them are named "Champ". And there are no more Institutes of Adult Entertainment in Richford.

Monsters are not native to New England waterways. Back in the time of the great Republic of Vermont, when Vermont was an Independent Country and besieged by imperious New Yorkers, it was Ethan Allen, a man of many fine accomplishments despite his eventual support for joining the Union, who formed a Secret Society charged with the clandestine importation, with total disregard to EPA regulations, of a breeding pair of monsters from Scotland. The purpose and training of which was to harass the New York Navy on Lake Champlain should it ever prove necessary.

The monsters, a common variety of Plesiosaur, were secured and trained to surface only at night and in response to their proper names, which are Gaelic, not renderable in the English alphabet, and secret from even Native Vermonters. It is not known for certain, outside of the Secret Society, whether the underwater monsters were ever activated. Perhaps one day a Secret History of New York will be published with tales of terrifying attacks on arms bearing freighters and vessels of war on Lake Champlain by Beasts as if from the Apocalypse. Then the Secret History of Vermont will have to be updated to respond with, "What rubbish."

Plesiosaurs are psychologically much like well-kept dogs: happy, trainable, and eager to please. Training is accomplished by being firm when they do it wrong and affectionate and rewarding, with fish, when they do it right. The first thing one trains a plesiosaur to do is, "Stay Down!" Having 20 tons of cold-blooded reptile playfully crash down on your boat is enough to ruin your whole day. Training for military action is the opposite of what one might think. Instead of associating ships, cannons, and a particular flag design as bad things that must be treated aggressively, the monsters are trained to see them as "things to play with that it's OK to jump on". I doubt that the chronicles of the survivors of such an "attack" would mention just how happy and excited the monsters appeared as they inadvertently crushed their new playmate into splinters.

Over the years the monsters were trained to recognize the naval flags of whatever entity seemed to be a threat at the time. After New York was subdued, England, Canada, France, the Confederacy, Germany, Japan, Italy, Korea, the Soviet Union, Cuba, Vietnam, Iran, Iraq, and Quebec all took turns being on the monsters' play list. At one point a pair of adolescent monsters were moved from Lake Champlain to Lake Memphremagog to guard the border in north central Vermont, much to relief of their parents. Rumors that the dome of the Vermont capitol building in Montpelier is plated with gold found in a Nazi submarine captured in Lake Champlain by the monsters during the latter part of World War II remain unsubstantiated at this time.

The Secret Society still keeps the existence of the monsters a secret lest they be discovered by the Montpelier Legislature and taxed to create a Department of Monster Management. Occasionally a young monster surfaces during the day, on a dare from other young monsters, and gets its picture taken. The Secret Society then goes into emergency mode and floods the media with stories about how logs, waves, boats, seagulls, schools of fish, single fish, shadows, clouds, and mirages can all be made to resemble a hypothetical monster if you squint your eyes hard enough. For those who refuse to take the hint and keep on harping about what they saw the Secret Society demonstrates these nifty pen-like things they have that flash red and ... what was I writing about?

The tendency for non-horizontal surfaces to always slant upwards is a

peculiarity of Vermont terrain that has been alluded to from time to

time in this book. In Vermont when a grandfather tells a grandson,

"Sonny, when I was your age I had to walk to school every day and it

was uphill both ways." the grandchild rolls his eyes, not because he's

being fed another line, but because Grampy is again belaboring the

obvious.

The tendency for non-horizontal surfaces to always slant upwards is a

peculiarity of Vermont terrain that has been alluded to from time to

time in this book. In Vermont when a grandfather tells a grandson,

"Sonny, when I was your age I had to walk to school every day and it

was uphill both ways." the grandchild rolls his eyes, not because he's

being fed another line, but because Grampy is again belaboring the

obvious.

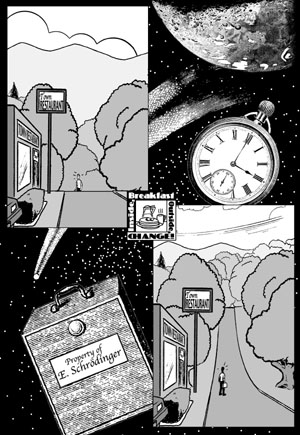

How is this possible? The answer involves quantum mechanics, the properties of subatomic particles, potentially dead cats, and the Burlington Free Press. In the ivory tower world of academia there are currently only five people with the intellect required to comprehend the situation. Fortunately there are no ivory towers in Vermont so the rest of us should have no problem with it.

In quantum mechanic circles it is a rule of thumb that all possible states exist until the probability wave function is collapsed by an observer and one of the states gets cruelly singled out by the rest to join the other unhappy states that comprise reality. The classic demonstration of this is called "Schrodinger's Cat" which is a thought experiment in which one puts a cat into a closed box along with a vial of poisonous gas and a mechanism that has a random 50-50 chance of breaking the vial in a certain time, say one hour. Do this and wait for an hour. What do you get?

The obvious answer is that you get a lawsuit from the S.P.C.A. In the ivory tower world of academia however what you get is a cat that is both dead and alive at the same time until you open the box. By opening the box and looking inside you "collapse the probability wave function" and get either a dead cat and a lungful of poisonous gas, or a compact mass of muscles, teeth, and claws trying to impress upon you its opinion on being locked up in a box for an hour.

The point being that the cat is neither dead nor alive before you open the lid and observe what's inside. The cat is in a weird state of being both at the same time.

A critical factor of the experiment is the random mechanism that may or may not break the vial of poisonous gas. For the experiment to work right in the quantum mechanical sense the random mechanism has to be really random. The classic random mechanism uses a radioactive atom as a trigger. If the radioactive atom decays within its half-life then the cat dies too, otherwise the cat lives on and can be reused in the next experiment.

Weird quantum mechanical effects, like both sides of an either-or situation being true at the same time, are generally only observed at the atomic and subatomic level because they require random events that are usually only exist at the atomic and subatomic level. In Vermont however there is a macroscopic random process of such a large magnitude that quantum effects become a fact of everyday life. That process is the Burlington Free Press weather forecast.

Every day the Burlington Free Press prints a weather forecast. Every day thousands of people in Vermont buy the Burlington Free Press and read the weather forecast. Every day the weather forecast in the Burlington Free Press has absolutely no correlation to the weather that day. The number of people who daily observe the completely random process of the Burlington Free Press weather forecast vis-a-vis the actual weather creates an incredible quantum mechanical stress that is discharged into the ground like lightning. As a result the ground in Vermont has some surprising properties.

Obviously not all locales in Vermont have the "uphill both ways" property otherwise Vermont ski resorts would have a much more difficult advertising job to do. Quantum mechanics (the people, not the theory) guess that this is because there are enough foreign skiers who don't read the Burlington Free Press to dilute the effect. Otherwise it is readily observed that, "On average, any given route in Vermont goes uphill." This is because when one sets out to go somewhere in Vermont all possible route-states exist at the same time. When one decides where to go and how to get there the probability wave function collapses and the second most improbable route-state is chosen: A route-state that goes uphill even if one went uphill to get where one happens to be and is now going back.

It is the second law of thermodynamics, "There's no such thing as a free lunch." that prevents routes from going downhill in both directions.

There are other effects of the quantum imbalance in Vermont. One is that despite the fact there are a finite number of miles of interstate highway in Vermont, repaving the interstate highway is an infinitely long process. Another is that regardless how low the min-max thermometer at the author's cabin indicates, the next day at breakfast there's someone at the Town Restaurant who claims that it was colder at his or her house that night.

It is not well known that golf is the Vermont State Sport. Even the Town of Richford has a full-time golf course. Towns that can't support a full-time golf course often have numerous part-time golf courses for that brief period of time between harvesting the hay on a field and the grass growing up again. Coordinating the harvesting in such Towns makes up a fair percentage of the Town Clerk's summer job responsibilities. Really good Town Clerks arrange it so that you can play the first nine holes on a field that's just getting too grown up and the second nine holes on a field that's just been harvested with the tree line separating the two fields making a good obstacle. Such Clerks are in great demand and command high salaries and good benefits.

The popularity of golf in Vermont doesn't get much media attention because the media tries hard not to be around during the time that most of the golf is played. When the media does happen to be around it sees men and women appropriately dressed for the course, golf carts, refreshing cool drinks, and the usual golf paraphernalia. In Vermont however you can only play golf like that for about 15 days each year. Most of the rest of the time the media would see men and women appropriately dressed for standing out in the middle of a snow-packed field with the temperature and wind solidifying everything in sight, snow shoes, snow mobiles, refreshing hot drinks, and the usual golf paraphernalia. If the media was persistent it would even see men and women appropriately dressed for wading through a large mud pit, amphibious ATV's with multiple sets of balloon tires, very large amounts of refreshing alcoholic drinks, and the usual golf paraphernalia. Vermonters take their golf seriously. Little things like the ruts made by the skidder that was called out to pull the course zamboni out of a sinkhole aren't permitted to get in the way.

The Late Great Unpleasantness was brought about by the introduction of the fluorescent orange golf ball which substantially changed the character of winter golf. One side insisted that colored golf balls were a loathsome and whorish innovation of the Flatlanders and their introduction was a poisoned arrow aimed directly at the minds of the youthful and productive citizens of Vermont to weaken them and lead them astray from the path of independence and righteousness. The other side said, "Cool! All that and we can actually see the ball!" The conflict was immediate and shortly the golf courses segregated themselves into "White" and "Colored" to keep the number of fights down. The only people that each side hated worse than the other side was the very small faction that called for tolerance and peaceful co-existence.

Everyone was having a wonderful time when disaster struck. Someone accidentally mentioned the issue within earshot of a member of the Montpelier Legislature. The Legislature immediately put aside any potentially harmless work and concentrated for the remainder of the session on its then magnum opus: Act 4: A Series of Statues to Regulate and Normalize the Sport of Golf in Vermont. The high points of Act 4 included:

It is when Vermonters are faced with the intolerable that their best qualities shine forth. When Act 4 was signed into law the population of Vermont, in a gesture subsequently known as Vermont's Finest Hour, quietly and democratically de-elected the entire Montpelier government. Some former members of the Montpelier Legislature were de-elected so hard they were never heard from or seen again. Others resurfaced north of the border where they spent their time in the smoke-filled back rooms of the Parti Quebecois headquarters dreaming of and elaborating on the post-separation plans of conquest.

Act 4 was repealed and forgotten. The only remnant is the tradition of crying "Four!" before a stroke.

Being large animals moose had a particularly difficult time of it when the Burlington Free Press started publishing daily weather forecasts and making everything uphill both ways. After putting up with it for a few years the moose population in Vermont decided to take advantage of the new environment in a particularly elegant manner. I am pleased to reveal their discovery which is a breakthrough in modern physics: The Unified Quantum Moose Theory.

Moose have always been very quantum animals. Either there's a moose in front of you or there isn't. No doubt about it. When the quantum fabric of Vermont was weakened by the Free Press' weather forecasts, individual moose discovered that they could teleport themselves by shifting into quantum phase space. Once you understand how it works teleportation is really very easy. All you have to do is reduce the probability of being in your current location to zero while simultaneously increasing the probability of being somewhere else to a certainty. Moose seem to have a knack for it.

Moose also discovered that it's possible to live in quantum phase space which turns out to be handy during difficult times like hunting season. Eventually the entire moose population in Vermont emigrated to quantum phase space, returning to our reality only occasionally for a "vacation in the old country" or when accidentally precipitated by an observer.

Remember that the role of an observer is very important in quantum matters. Nothing can be said to have really happened until it's been observed. This is a minor nuisance for moose because an intent observer in Vermont can force a moose to appear out of quantum phase space just by being really observant.

Of course it's extremely unlikely that a 180 pound person will precipitate a 2000 pound moose even under the best conditions. The rare times one sees a moose along the interstate it's certainly because several people in different cars were all looking at the same patch of ground at the same time and their combined observational power forced the moose to appear.

So if moose can be said to hardly exist in Vermont any more, what's with all those signs on the interstate? Blame the Montpelier Legislature. When the Vermont Department of Moose Management was made aware of the Unified Quantum Moose Theory it reasoned that a moose in quantum phase space could be thought of as occupying the entire State because no matter where you point, the probability, however low, of the moose being there, is the same. Therefore, if a moose is everywhere then it could be anywhere, and if a moose is anywhere then the VDMM might as well put up all of its Moose signs on the interstate where they're highly visible and, as a gesture of solidarity with the Vermont Department of Interstate Management, it'll inconvenience the maximum number of commuters when the signs are installed and maintained.

Reported sightings are rare not because sightings are rare, but because people don't bother. Reporting seeing a catamount in Vermont is like reporting seeing an ATV. If you reported every one you saw you'd never get any work done. Certain woodlands in Vermont are crawling with mountain lions yet when someone discovers a partially eaten deer in the woods or a downed cow, wild dogs always end up with the official blame.

A hundred years ago the common Vermont Mountain Lion was subjected to some intense evolutionary pressure by virtue of Montpelier's policy of paying a generous bounty for every one shot. When the bounty money ran out the Montpelier Legislature reasoned that the mountain lion must have become extinct and declared it a retroactively endangered species, making shooting one a felony.

This was just fine with the mountain lions who had in the meantime evolved into a new species that instinctively avoids being seen by members of the Montpelier Legislature, members of the Vermont Department of Mountain Lion Management (still going on strong despite its officially extinct subject matter), game wardens, UVM zoology professors, and anyone else who might be in a position to officially recognize one.

Occasionally a kind-hearted person tries to restore to the catamount some kind of official existence in under the theory the species can only benefit from the protection and management of the wise inhabitants of Montpelier, but the Libertarian Mountain Lion is having none of it. Mountain Lions are practically the only living entities in Vermont who don't pay taxes.

Thought to be an evolutionary offshoot of the common woodpecker, the tinpecker is adapted to survive in climates where the frozen trees are harder than locally available metal artifacts. Very little is actually known about the tinpecker, like what they eat, what they make their nests out of, and the composition of their eggshells. The only interaction so far between Vermont ornithologists and tinpeckers is when the former swear at the latter at 4:30 in the morning.

It is true that one does not generally see great displays of mundane wealth in Vermont. That doesn't mean that such wealth doesn't exist, it just means that it's well invested and not obvious. Vermont has a boom-bust cycle that has served for centuries as a reliable and comforting source of income for those who are wise and disciplined enough to take advantage of it. The cycle depends on two critical components:

Here's how it works. Remember this is a cycle so the "starting point" here is arbitrary:

(Author's note: Unlike the rest of the Secret History of Vermont which was revealed to the author by real Native Vermonters, the author, who lives in a log cabin made from logs of spruce and balsam, figured this part out for himself.)

Ethan Allen's reputation never really recovered from his support for joining the Union and the wisdom of the idea is still debated among Native Vermonters who, in any event, never gave up the apparatus for international meddling.

The first task of the Vermont Department of International Management was to sort out the squabble between New York and New Hampshire who both claimed the exclusive right to tax the Republic (of Vermont). This was handled skillfully by Ethan Allen who alternately played one side off against the other when he wasn't claiming that he had arranged for bigger countries to provide protection from both. Eventually the two U.S. states decided it was best if the small, but rambunctious, Republic was just ignored.

The VDIM helped arrange the terms for joining the Union and then turned its attention almost exclusively to what eventually became the unhappy Canadian Province of Quebec. Vermont's first concern was to reassure Quebec that trade across the Vermont border would continue unhindered regardless of any silly rules, regulations, or tariffs set up by the U.S. Federal Government.

Poor Quebec. The proud French colony was essentially traded to England as a minor peace treaty concession and the psyche of the region never recovered. Quebec never had its fifteen years of Statehood. Surrounded by its traditional enemies without support from its progenitor the best Quebec could do was to try to maintain its culture while making the Rest of Canada (a proxy target with England being beyond reach) pay and pay and pay.

This suits Vermont just fine. In terms of honorable commerce, Vermont counts Fair Trade to be second only to Fair Trade with a Partner With Unfortunate Internal Difficulties.

Canada was confederated in 1867 and still doesn't have its economic act together. Canada is full of smart and industrious people and has vast natural resources and is still sort of a minor economic appendage to the U.S., like an extra toe on one foot. Every time the Canadian economy starts to get a little momentum Quebec pops up and stops it in its tracks.

When the economy is slow Quebec hunkers down and lives off its generous Canadian federal subsidies. When the economy is revving up Quebec asks "Who needs Canada?" and starts talking about independence. Neither state is attractive to disappointed investors who would otherwise flood Canada and Quebec with money.

On the other hand Unfortunate Internal Difficulties is attractive if one's goal is to buy stuff cheap, and Vermonters have traditionally tended towards the philosophy of "get rich by spending less" rather than "get rich by investing more". Vermonters like it when their dollar is worth $1.30 in Canada and want to see it stay that way.

Canada is a small country, as countries go, but Vermont is an even smaller State, as states go. There's very little that Vermont can do to impress Canada. Quebec by itself is huge compared to Vermont but Quebec is desperate for international recognition and tends to treat other non-sovereign states the way it wishes it were treated. Therefore Vermont's influence is much greater than it should be. Vermont's French speaking population, mostly in the Towns along the Quebec border, helps a lot too.

The U.S. Federal Government takes a dim view of its states prosecuting their own foreign policies so the Vermont Department of International Management has to be subtle. Most of the VDIM's work is propping up the Parti Quebecois (the Quebec Independence Party) when its spirits or finances are flagging. Does the PQ need funds? Then Vermont signs an expensive contract for electricity with Hydro-Quebec, a division of the Quebec provincial government, which is usually run by the PQ. Is Canada's legal maneuvering getting the better of Quebec? Then Vermont's Lieutenant Governor gives a speech (in French) to the Quebec's provincial legislature (the "National Assembly") on the benefits of free trade.

Vermont thinks of Canada and Quebec like a maple sugar boiling table. With an unlimited supply of sap (Canada's native resources) and a well tended fire (Unfortunate Internal Difficulties) Vermont can extract as much maple syrup as it wants.

Radiocarbon dating is a way cool technique for figuring out how old

stuff is. It works by measuring the amount of radioactive carbon-14 in

a sample of something that was once alive. All living things have a

small but constant amount of carbon-14 in them. When they die the

carbon-14 slowly decays. By measuring the amount of carbon-14 left in

a sample you can tell when it died.

Radiocarbon dating is a way cool technique for figuring out how old

stuff is. It works by measuring the amount of radioactive carbon-14 in

a sample of something that was once alive. All living things have a

small but constant amount of carbon-14 in them. When they die the

carbon-14 slowly decays. By measuring the amount of carbon-14 left in

a sample you can tell when it died.

Archaeologists invented radiocarbon dating and now there are labs that'll do it for a fee. You send them a sample of something you've dug up and they'll tell you how old it is. Unless you're from Vermont. Radiocarbon dating labs don't accept samples from Vermont any more.

The problem is homework. Every year freshman archaeological students are given the following summer project: Find the oldest sample you can and send it in to a radiocarbon dating lab to be dated. So every summer hundreds of students visit their grandmothers, duck down into the deepest darkest corner of the basement, and scrape into a sample bag the oldest driest sliver of wood they can find.

Hundreds of sample bags are mailed to various labs (probably all owned by the Archaeology Professors) and shortly after the results are mailed back: 15 years, 67 years, 3 months (nice rec room), 110 years, 29 years, 30,000 years, etc. It's results like that last one that caused the problem for invariably the student would raise a stink and demand his or her money back. It didn't take long for the radiocarbon dating labs to figure out that all such anomalous results came from Vermont and to blacklist the entire State.

It's not that Vermont isn't full of jokers. (Drive a car with out-of-state plates and ask directions from someone in Vermont sometime. Please!) It's just that the conclusion that every single Vermont archaeology student independently decides to pull exactly the same prank is one that only an Archaeology Professor or Radiocarbon Lab Owner would come to.

The other conclusion, that the canning jar racks in grandma's basement are 30,000 years old, is one of those things that's so completely and totally obvious that the maintainers of the Secret History don't have the slightest worry of it ever being discovered.

Not all Vermont archaeology students send out 30,000 year old samples to be dated, just those who attend out-of-state schools and who are therefore disqualified from being taught the Secret History. Anyone in the know, of course, wouldn't be so stupid.

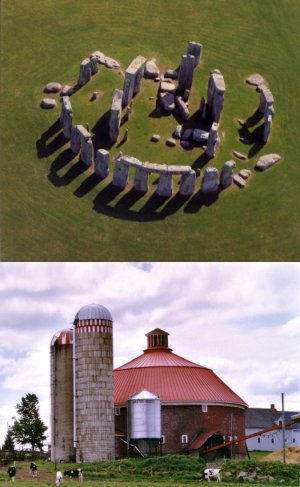

30,000 years ago a race of mysterious people now known as the Picts occupied most of the island now known as England. The Picts had an extremely high level of civilization and were practically worshipped as gods by the other races who were in awe of the Picts' knowledge of farming, technology, medicine, and commerce. Only the Picts knew the secret of distilling sugar from trees. The Picts built mostly with wood which is why there's hardly any trace of them left, but occasionally they built with stone and the remains of some of those structures survive to this day. The Picts' unit of government was the homestead and anyone who felt the need could go out to the frontier, clear some land, and build a homestead of his or her own. The Picts abruptly disappeared from England leaving little evidence of their existence.

As always happens to civilizations that last any length of time, the climate changed. The poles got colder, water started freezing into ice, and the sea level dropped to the point where a land bridge between England and Europe reappeared. The Picts remembered this bridge as the one upon which they traveled to England thousands of years prior. This time is was barbarians from Europe who crossed the bridge and the Picts could see the handwriting on the wall. Pretty soon there would be a Legislature, Zoning, Taxes, debates about Universal Coverage, and why hang around for that? Particularly since the frontier hereabouts is getting a little sparse anyway and we all know that there's an entirely empty continent just a few thousand miles west.

So the Picts built a huge fleet of ships, loaded everything that could be moved onto them, and sailed to the new world. They landed off of what is now known as the coast of Maine but decided to venture further west until they were completely satisfied. A few hundred miles later they came across the perfect combination of mountains, rivers, and valleys, and made it their new home which they named "Vermont."

The word "Vermont" derives from Olde Neanderthale but modern day scholars are divided as to its precise meaning. Some say that it comes from "ver mont" which in Olde Neanderthale means "Heaven on Earth" but others insist that it really comes from "verm ont" which means "Any place that if you stay there during the winter you must have rocks in your head." Olde Neanderthale is a very pithy language.

The emigration of the Picts to North America completely devastated the English economy of the time and created the English legend of a rich, all-knowing, and all-powerful race of magical elves who live on an unobtainable island somewhere "in the west."

It was a few thousand years later that the same shift in climate that re-revealed the Europe-to-England land bridge revealed the Siberia-to-Alaska land bridge and people from Asia crossed to Northern North America and slowly began to expand south. When the Native Vermonters finally encountered the newcomers they were welcomed and the two races exchanged what bits of culture and technology they could, which wasn't much since both were already completely independent and self-sufficient.

By that time the Native Vermonters had an old, established, and stable system of homesteads, roads, and Towns. There was plenty of extra space on which the newcomers, the menfolk of whom were admired by the Native Vermont men because they didn't have to shave, occupied seasonally as was their custom.

This situation lasted for another few thousand of years until Columbus discovered America and all hell broke loose. The barbarians from England and Europe emigrated seemingly all at once. The Native Vermonters were racially close enough to the barbarians to be mistaken for "settlers who got there first" but the "Indians" were massacred nearly to the point of extinction.

The barbarians brought their system of government with them and, to prevent the new government from gaining the power of tens of thousands of years of civilization, the true History of Vermont was made Secret as previously described.

The relationship between the Native Vermonters and the "Indians" suffered grievously. The "Indians" blamed the Native Vermonters for not assisting them while they were being attacked, but the Native Vermonters didn't want to get involved in the barbarians' politics (English vs. French) while the "Indians" seemed to have all allied with one side or another. As a result the "Indians" lumped all "non-Indians", Native Vermonters and barbarians, into a single category: oppressors.

But note that the State of Vermont still does not recognize any "Indian" tribe of being native to Vermont.